Could Micro Housing alleviate the housing crisis or is it a passing fad?

Urbanissta’s Legal Beagle – Farhana Hussain, examines the topic of micro housing in the UK.

- What are micro homes?

- Who would be the target audience?

- Has the need for larger homes become less of a priority?

- House costs and affordability

Farhana’s findings…

I recently submitted my dissertation and it was centred upon whether micro housing could solve the housing crisis. I’ve observed a number of micro housing schemes popping up across London, so, I thought, why not do a blog on my findings and address what’s been making the headlines. Is there room for micro homes in this current climate, how affordable are they and could they really alleviate the housing crisis?

Context

I find that there is a common perception that rising housing prices have forced developers to sacrifice space and quality by seeking higher density and higher revenue per sqf to offset rising land value and construction costs and so offer affordable housing. It is thus widely believed that the introduction of micro housing capitalises on this pattern. Apartments and houses that are small by traditional standards are currently being sold at 20 per cent below market rate in London, and are now being considered in urbanising locales, particularly high-density cities where affordability is stretched.

What are Micro Homes?

A working definition of micro housing is a unit of less than 500 sq.ft, with a fully functioning kitchen, bathroom and WC. A small room at 160 sq.ft with a communal kitchen, bathroom, etc., is not to be considered a micro home as it does not fall under this definition. It is difficult to pinpoint the ideal unit size. Furthermore, for micro homes to gain popularity on a meaningful scale, and so potentially alleviate the housing crisis, it is important to understand that these homes need to be targeted at a specific audience and serve a specific purpose, particularly if they fall below minimum space standards.

Who would be the target audience?

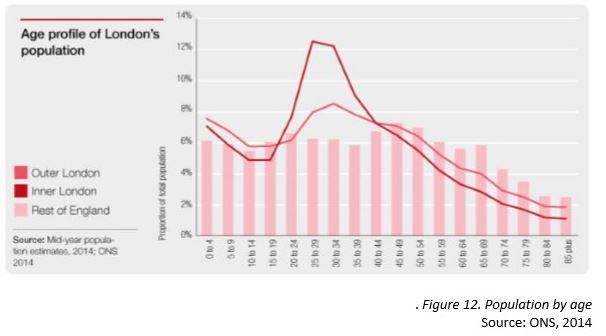

London has a target to deliver a minimum of 55,000 homes per annum for the next decade. As in the image below, the biggest age group in Inner London is 25 to 29 olds and in Outer London it is 30 to 34. The Households and Household Composition in England and Wales report for 2001-2011 showed an increase of 564 single-person households, the highest proportion of which was in London (35%). With the highest population in London being below the age of 30, it is evident that not enough is being done to house this audience. This is reinforced by the 37% over the ten-year period in the number of 20 to 34-olds living with parents.

Has the need for larger homes become less of a priority?

Yes and no.

The needs of society are not the same as they were at the time of two World Wars. The economic status of the country, digitisation, lifestyle changes and under-occupancy may all have contributed to the reduction in minimum standards, while the increase in one-bedroom households is more likely due to cost limitations rather than personal preference. Nevertheless, the evident demand for one-bedroom homes in London, where the largest age demographic is between 25 and 29, indicates that there may be a market for micro home. Micro housing appeals mainly to younger audiences for whom location, economics and privacy are important, or to older generations looking to downsize.

House costs and affordability

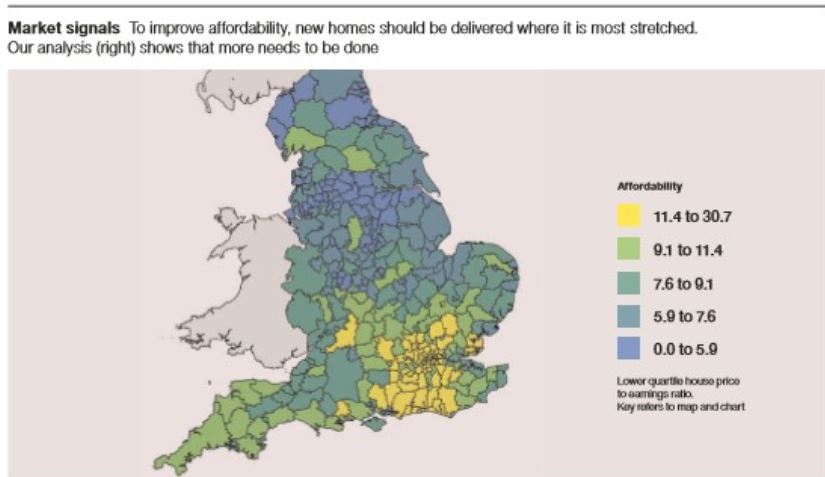

Due to the housing crisis, housing costs of all types and tenures are rapidly increasing across the UK, particularly in London and the South East. Affordability, however, is not just confined to private ownership: tenures of all types are now disproportionate compared to average income, with almost three million households in the UK now spending more than a third of their income on housing. Thus, it is widely agreed that the supply of affordable housing is at an historic low and requires urgent policy intervention. In order to improve affordability, it is estimated that 300,000 new homes are needed in England every year, more than double the current rate of building.

London has seen a slight increase in affordable housing, with many local authorities making the provision of affordable housing a prerequisite in securing planning permission. There has been a rise in shared ownership and sub-market rented homes, yet questions remain over just how affordable they really are, and to whom. Some of these ‘affordable’ homes require the occupiers to be on incomes over £60,000, double the average London household income. Clarity over what is meant by affordable housing is therefore paramount, and to whom we are relativising the housing cost. With middle-income households demanding homes at 60-80% of market prices, this by no means infers a reduction in the need for social rent for low-income households.

Within the overarching definition, the London Plan’s supporting texts set out criteria to assess affordability based on different schemes:

Affordable housing includes social rented, affordable rented and intermediate housing… and should: (a) meet the needs of eligible households including availability at a cost low enough for them to afford, determined with regard to local incomes and local house prices; (b) include provisions for the home to remain at an affordable price for future eligible households; or (c) if these restrictions are lifted, for the subsidy to be recycled for alternatively (London Plan, 2016).

Further details for each scheme stipulated by the policy are listed in the table below

| Type of housing | Criteria |

| Social rented housing | Guideline target rents are determined through the national rent regime or provided by other bodies under equivalent rental arrangements to the above, agreed with the local authority or with the Homes and Communities Agency. |

| Affordable rented housing | Affordable rent is subject to rent controls that require a rent of no more than 80% of the local market rent. |

| Intermediate housing | Affordable to households whose annual income is in the range £18,100-£64,000. Two bedrooms, suitable for families; the upper end of this range will be extended to £74,000. |

| London living rent | Yet to be rolled out by the government. |

Despite the government’s efforts and the 56% increase in residential consents, closer analysis indicates that there has not been any increase in the areas where affordability is most stretched ( see image below. Source: Savills, 2017).

Figure 14. Affordability in England

Source: Savills, 2017

It is, therefore necessary for developers to take advantage of market demand in order to drive the success of their market-sale programmes and generate subsidy for affordable housing. Priorities need to be shifted from aimlessly building homes to homes being built where they are most needed. Ultimately, for micro homes to make a meaningful contribution to the housing market, they should be deployed in areas of stretched affordability, particularly in London and the South East.

Can Micro Housing alleviate the housing crisis?

The UK housing crisis is made up of a number of interconnected issues, including the lack of construction workers, reduced LPA powers, a lack of transparency, increased demand through deregulation, and lax policy-making. Some have argued that the housing reform to this point, if anything, has exacerbated the problem. This would suggest that the government need to look first at stabilising the market before the crisis can be solved in the long term before diving head first into eliminating the crisis.

As highlighted above, 25 to 29-olds are the largest age demographic in Inner London; in Outer London, it is 30-34 year olds. The Households and Household Composition in England and Wales reported an increase of 564,000 single-person households between 2001 and 2011, the highest proportion of which is in London holding (35%). Taking both the above indicators together, it is clear that not enough is being done to house the under-thirty market in London. Come micro housing developers are marketing micro homes as a potential solution for Inner Londoners, a one-bed micro home is currently being marketed at over £200,000 (after 20% discount): this would require an average annual income of at least £40-50,000. I n reality, the average for those aged between 25 and 29 is £28,000. This would suggest, therefore, that the micro housing schemes currently being implemented in London are not serving their original purpose. Moreover, it is understood that the Mayor of London has already invested millions of pounds into the development of micro homes, without any clearly-advertised criteria against which these schemes will be assessed. Given that such schemes are in their relative infancy, it would appear that LPAs are taking the initiative without empirical supporting evidence.

Conclusion

It appears, in practice, that current micro housing developments are solely targeting those on the higher end of this scale, effectively ignoring the majority of those who fall within it. As such, a new definition will need to be considered. Affordability must take into account expenditure, commuting costs, dependents, and a number of other socio-cultural determinants. Given that salaries and house prices differ from borough to borough, there is an argument for local authorities to be given greater powers to assess what is genuinely affordable in their areas, rather than being held to a standardised yet ultimately ambiguous definition. Furthermore, given how space standards have decreased over time, and will most likely continue to do so, the definition of micro housing may need to shift with the times as well: unless micro units are launched as a separate entity or affordable housing scheme, they may no longer by necessary as small one-bedroom properties become the norm.

Don’t miss out on Farhana’s case law reviews. Tracking planning decisions and proposed developments. Read more about Urbanissta’s Legal Beagle.